They weren’t all born bad. Some of horror’s most iconic monsters aren’t villains at all — they’re victims of circumstance, cruelty, or their own humanity. Before we grab the pitchforks and torches, it’s time to look closer at the so-called beasts who’ve been misunderstood for over a century.

Because sometimes, the real monsters are the ones holding the flaming torches.

Welcome to the Monster Empathy Project — where we dare to ask, what if the creature didn’t deserve to die?

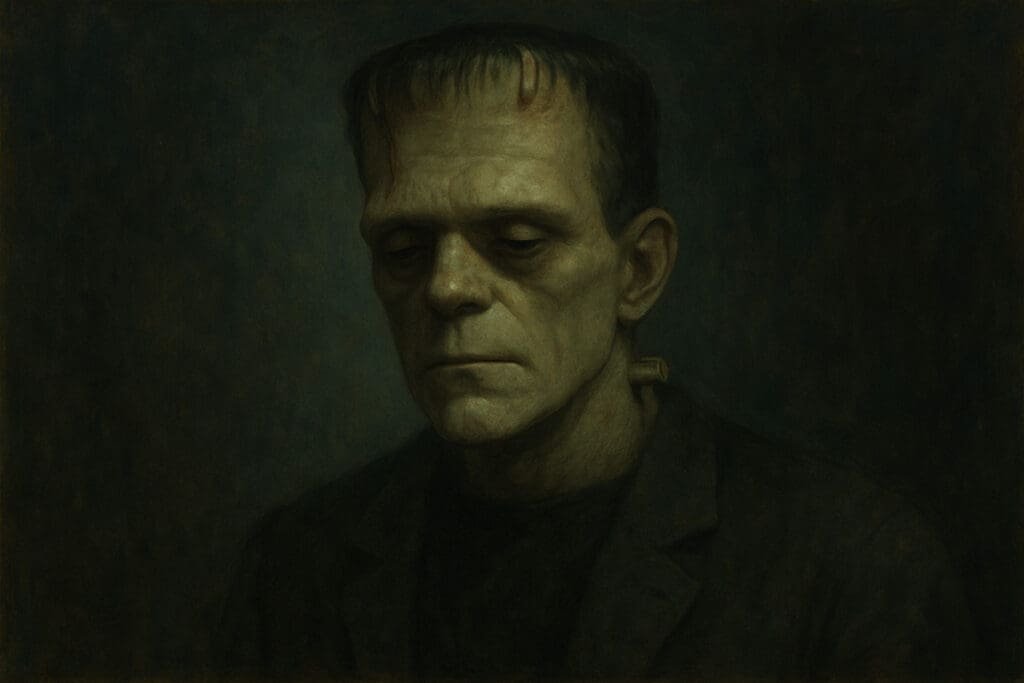

Frankenstein’s Creature: The Original Outsider

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein remains the blueprint for tragic horror. The Creature is born into a world that hates him on sight — unloved, unaccepted, and cast aside by his creator. His sin isn’t violence or vanity. It’s wanting to belong.

Every version of the Creature — from Boris Karloff’s mournful giant in Frankenstein (1931) to the poetic, tormented soul in Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) — drives home the same point: rejection breeds monstrosity. Shelley didn’t write a story about science gone wrong. She wrote about what happens when compassion fails. The horror isn’t the Creature’s existence — it’s the world’s cruelty in response to it.

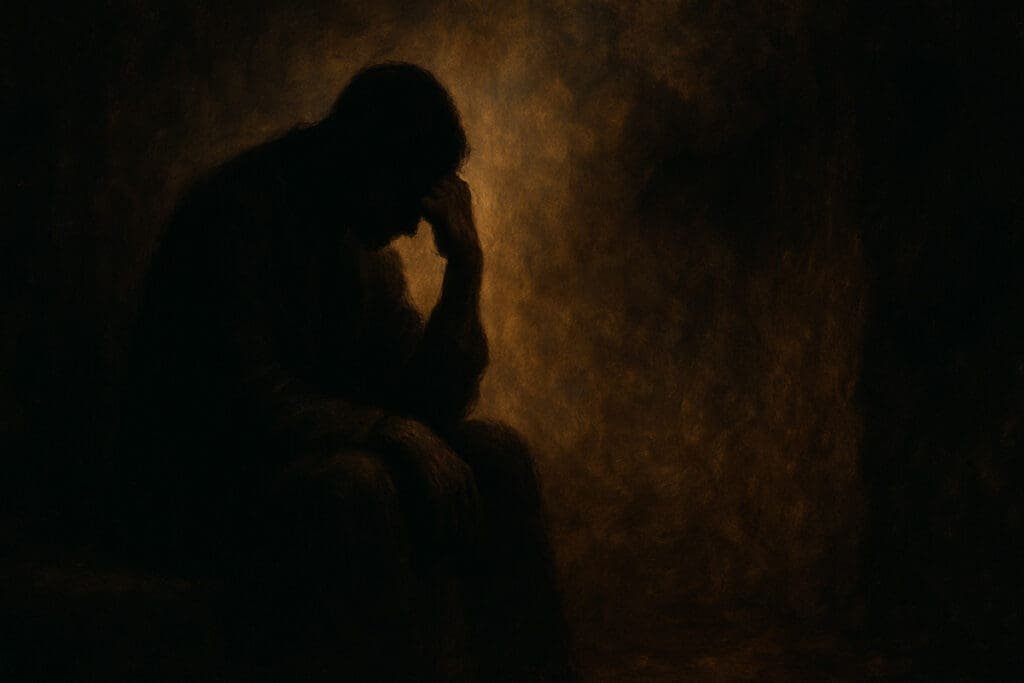

The Wolfman: The Beast Within

Larry Talbot, the doomed protagonist of The Wolf Man (1941), isn’t a villain; he’s a man cursed by fate. His transformation is painful, both physically and psychologically. He dreads his power, fears his reflection, and becomes his own worst enemy.

The Wolfman’s curse isn’t just lycanthropy — it’s guilt, shame, and a loss of control. You can read his story as an allegory for trauma, addiction, or the mental toll of repression. The tragedy of the Wolfman isn’t that he becomes a beast; it’s that he remembers what it’s like to be human.

The Phantom of the Opera: Love and Loneliness in the Catacombs

Few monsters are as heartbreakingly human as the Phantom. His story — told in countless versions from Lon Chaney’s silent classic (1925) to the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical — is one of longing, not evil.

The Phantom is no supernatural being. He’s a man ostracized for his disfigurement, living beneath a world that refuses to see him. His mask hides more than scars — it hides a lifetime of humiliation and hurt. Beneath the melodrama lies a devastating truth: sometimes the most terrifying thing about a monster is how much they remind us of ourselves.

The Mummy: The Curse of Eternal Devotion

Imhotep, the resurrected priest of The Mummy (1932), isn’t rampaging for power — he’s chasing lost love. His story is one of obsession, grief, and devotion twisted by time. Every stride of his wrapped, weary body isn’t just menace — it’s mourning.

The Mummy turns horror into tragedy. It reminds us that even love, when denied or distorted, can curdle into monstrosity. Imhotep’s curse isn’t immortality. It’s remembering.

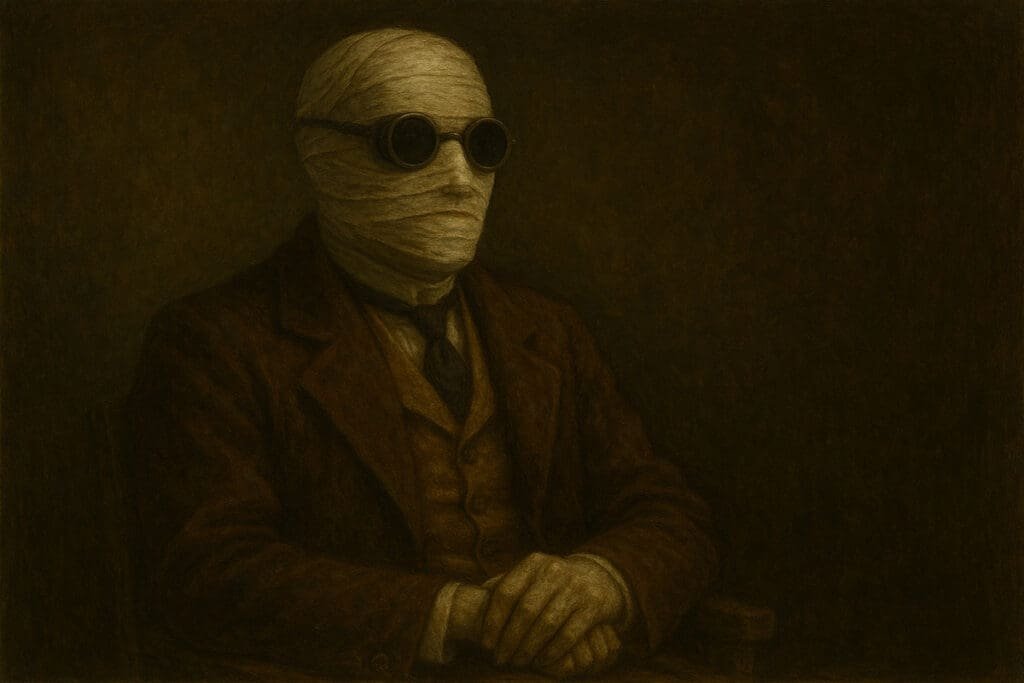

The Invisible Man: The Horror of Being Unseen

H.G. Wells’ Invisible Man (and James Whale’s 1933 film) gives us a different tragedy: isolation by choice. Griffin’s power grants him freedom, but it also unravels his sanity. The longer he remains unseen, the less human he becomes.

He’s not just a mad scientist — he’s a man consumed by the terror of being ignored. The Invisible Man is a metaphor for alienation and ego, warning that invisibility — literal or emotional — comes at a cost. When no one sees you, what’s left to stop you from vanishing altogether?

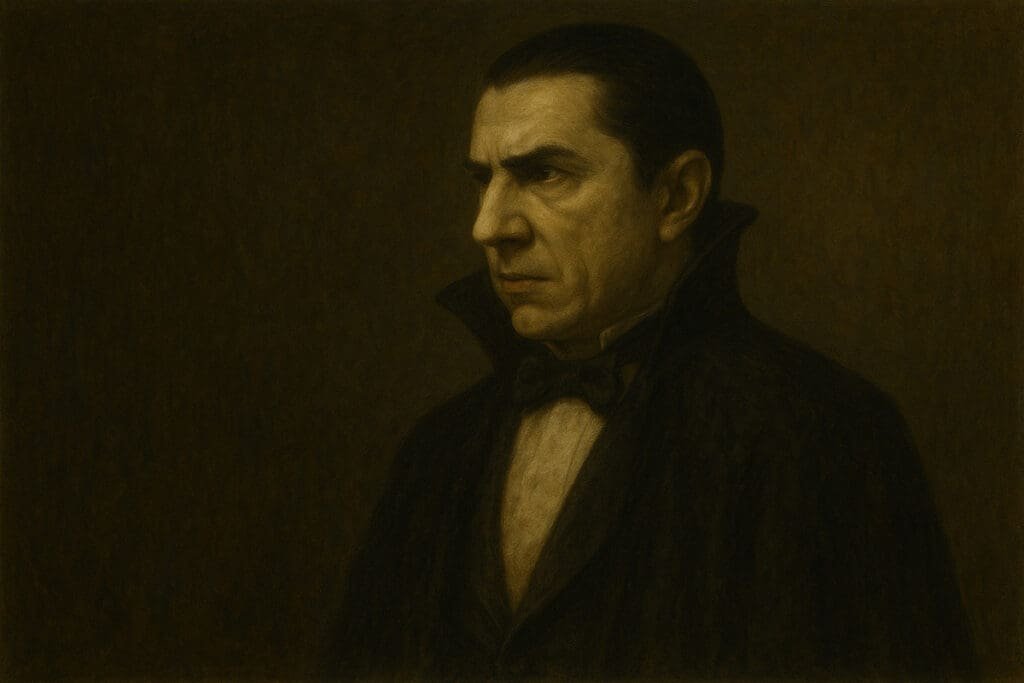

Dracula: The Eternal Outsider

Dracula is often painted as pure evil, but peel back the cape and you’ll find melancholy. The Count’s immortality is isolation; his hunger, a curse. Whether it’s Bela Lugosi’s suave menace or Gary Oldman’s heartbreakingly romantic portrayal in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), the subtext remains: eternal life without love is the real damnation.

He’s the aristocrat cut off from the world, cursed to consume rather than connect. His tragedy isn’t that he preys on humanity — it’s that he can never truly be part of it again.

Why We Pity the Monster

Classic monsters endure because they aren’t simple villains. They blur the line between human and other, victim and villain. Horror gives them shape, but empathy gives them meaning.

They speak to the pain of being different, misunderstood, or rejected. Frankenstein’s creature just wanted a friend. The Wolfman wanted peace. The Phantom wanted to be seen. Dracula wanted love. The Mummy wanted his heart back. Beneath the rotting bandages and fur and fangs, they all wanted the same thing we do — connection.

These monsters survive in popular culture because they hold up a mirror. Horror’s secret power has never been about jump scares. It’s about reflection — seeing ourselves in the thing we fear.

Modern Monsters, Modern Mirrors

Contemporary horror continues to explore this empathy for the monstrous. Guillermo del Toro, modern master of the misunderstood, has built his career on it. Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) made fascism the true monster. The Shape of Water (2017) turned a “creature from the deep” into a love story that won an Oscar.

Even Penny Dreadful (2014–2016) resurrected classic creatures with emotional depth. Frankenstein’s creation is portrayed as poetic and lonely, the Wolfman as guilt-ridden, the vampire as haunted by memory. These stories prove we’re still drawn to monsters not because they terrify us, but because they remind us that being human is terrifying enough.

Modern reimaginings like Let the Right One In (2008), Crimson Peak (2015), and The Lighthouse (2019) carry the same torch — blending empathy with unease. Horror today continues Shelley’s legacy: fear as a pathway to compassion.

Final Thoughts: The Humanity Beneath the Horror

It’s easy to love the scream, the shock, the spectacle. But the best horror — the timeless kind — comes from tragedy. From creatures who wanted only to be loved, accepted, or understood.

So the next time you sit down for a Universal Monster marathon, don’t just revel in the shadows. Look between them. There, in the sorrowful eyes of Frankenstein’s Creature or the mournful howl of the Wolfman, you’ll find something achingly familiar.

They are not the monsters we should fear. They are the monsters we already are.